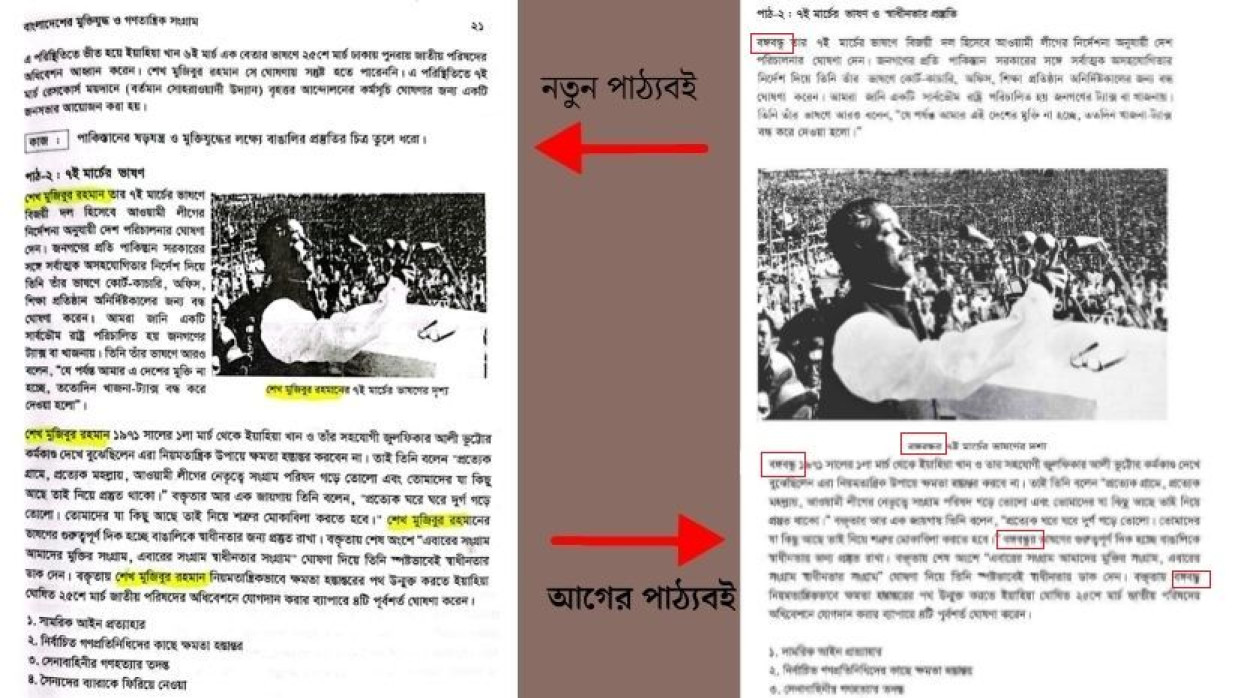

Baanglades’s Text book board removed the Bangabandhu

Dr. Lubna Ferdowsi

History is neither a weapon of revenge nor a file lying on a ruler’s desk to be opened and edited at will. It is the moral backbone of a nation, the framework upon which we understand who we were, where we stand today, and which path we must take tomorrow. When this backbone is repeatedly fractured and distorted, the state may appear to stand, but it collapses from within.

In Bangladesh, history has long been a hostage to political power. Governments change, and so do textbooks. Words are altered, symbols are dismantled, and sometimes reassembled in new configurations. This is often euphemized as “correction,” “balance,” or “depoliticization.” In reality, what happens is not neutrality but a steady erosion of collective memory. When history is written to serve the ruler, the shared memory of a nation becomes unstable, confused, and fragmented.

In this context, the removal of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s name and the title “Bangabandhu” from curricula cannot be dismissed as a mere administrative decision. Anyone who does so is either ignorant or disingenuous. The question here is political imagination. Benedict Anderson long ago observed that “a nation survives through shared memory, language, and symbols.” When those symbols are attacked, the nation itself is forced to be reimagined. This is memory politics, a direct intervention of power into history.

The role of Jamaat-e-Islami in this process is particularly significant. History shows that Jamaat was never the majority party in this land. Their influence never came from electoral strength but through gradual institutional penetration, education systems, religious spheres, legal frameworks, and more recently, the media. Political scientists describe this as “silent power,” where controlling memory and language is prioritized over winning votes.

Today, even outside formal government structures, their ideological influence pervades the state apparatus like a virus, leaving an indelible imprint on questions of 1971, the Liberation War, curricula, and national memory. This is not coincidental.

At the center of this memory struggle stands Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, inseparable from the titles “Bangabandhu” and “Father of the Nation.” The term “Bangabandhu” was neither invented by a party nor imposed by any government. It emerged organically from the masses during the 1969 uprising, following his release in the Agartala conspiracy case, when millions at Racecourse Ground chanted it. It was grassroots affection and political recognition, language of the people, not of power.

Historian Willem van Schendel notes that no leader in East Pakistan before 1971 had achieved such cross-class acceptance. Mujibur Rahman represents a leader who emerged from within the populace and ascended to the center of state authority without losing touch with his base.

The Liberation War was not a regional rebellion but part of the volatile geopolitics of the Cold War. On one side, the United States and China supported Pakistan; on the other, India and the Soviet Union counterbalanced. A flood of one million refugees drew international attention, placing Sheikh Mujibur at the center of political, moral, and diplomatic calculations.

He transitioned from subaltern leader to statesman, described by the global press as “a rare mass mandate in the post-colonial world.” India’s South Block saw him as a guarantor of regional stability; Moscow recognized the legitimacy of Bangladesh’s independence; and Western media acknowledged both his charisma and mandate. Time Magazine, BBC archives, and The Washington Post all reflect this recognition. The 1975 assassination disrupted Bangladesh’s external alignment, underscoring the international and regional significance of Mujibur’s memory.

Understanding Mujibur as a subaltern leader turned statesman is not sentimental or literary, it is a well-established analytical framework in history, political science, and international relations. He did not emerge from elite military or bureaucratic structures, but from the grassroots, peasants, workers, language movement activists, and lower-middle-class political workers. Ranajit Guha’s concept of subaltern leadership, where leaders emerge from below and rise to the center of state power through the lived experiences of ordinary people, finds its classic example in Mujibur. His political rhetoric in the 1950s and 1960s, the Six-Point Program, and organizational strategies exemplify this grassroots leadership (Guha, 1982; van Schendel, 2009).

Yet his historical significance did not stop there. In 1971, he emerged as a statesman, strategically leveraging international power balances. The Delhi-Moscow axis was integral to Bangladesh’s Liberation War, not incidental. The India–Soviet Treaty of Friendship (August 1971) reshaped South Asian power dynamics, with the democratically elected leader of East Pakistan at the center. Although imprisoned in Pakistan, Mujibur’s legitimacy in international diplomacy remained intact.

Gary J. Bass, in The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide, writes that “Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s 1970 electoral mandate made it increasingly impossible for the Western powers to support Pakistan’s genocide, giving India and the Soviet Union moral and political justification to intervene.”

This historical reality clarifies the meaning of the title “Father of the Nation.” It is not a domestic political invention, nor a post-1975 manufactured myth. Political science and nation-formation theory define this title as recognition of a leader who transforms a subjugated or colonized people into a distinct political nation. Historical analogues include Washington, Atatürk, Nehru, and Mandela. Scholars Willem van Schendel and Ayesha Jalal have both observed that in 1971, Bangladesh had no alternative political center, international recognition, diplomatic representation, and national legitimacy were all inseparable from Mujibur’s leadership.

Contemporary global media confirmed this. The New York Times described him as “the symbol of Bengali self-determination,” The Guardian called him “a rare post-colonial leader capable of translating popular legitimacy into international diplomacy,” and Le Monde interpreted Bangladesh’s Liberation War as the logical outcome of his political leadership.

These are not Awami League propaganda; they are historically documented international assessments.

In this light, dismissing the title “Father of the Nation” as entirely false or manufactured is intellectual dishonesty. It is not a subtle theoretical critique but a political slogan intended to obscure the history of nation-building and diminish the centrality of Mujibur in post-Liberation national identity. Attempts to manipulate historical language and symbols in this way are carefully strategic, aimed at blurring the pivotal role of the nation’s founder.

Yet the historical record is immutable. International diplomacy, global media, the overall structure of the Liberation War, and post-war state formation all document Sheikh Mujibur Rahman not merely as a party leader but as the architect of Bangladesh’s national identity.

Criticism of his governance is legitimate in democratic practice. However, such critique cannot negate his leadership in the Liberation War or his role as the nation’s founding father. US State Department and UN archives confirm that in 1971, international recognition of the Liberation War hinged on Mujibur’s central position.

All democratic actors, including former Presiden Ziaur Rahman, former Prime Minister Begum Khaleda Zia, and former President Ershad, acknowledged Mujibur as the founding father of Bangladesh. Such acknowledgment is essential for a healthy political culture. Unfortunately, that culture has eroded: while the Awami League institutionalized August 15 as a partisan event, Jamaat and its allies now seek to distort Mujibur’s legacy from the opposite end, even removing the “Bangabandhu” title from textbooks.

History does not vanish overnight. First, symbols are questioned. Then, language softens. Then crimes are relativized. Genocide becomes “conflict,” collaboration becomes “complexity.” This is how revisionism silently operates under the guise of balance.

Political differences will always exist. Leadership will be critiqued. Sheikh Mujibur is not beyond scrutiny. But a nation’s birth narrative cannot be erased. Bangladesh without Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is politically impossible. Whoever you are, whichever party you support, you must ethically acknowledge that he is the central pillar of Bangladesh’s national identity. This is documented truth, validated by popular participation and international recognition. Preserving this truth is not an act of partisan loyalty; it is a duty to history.